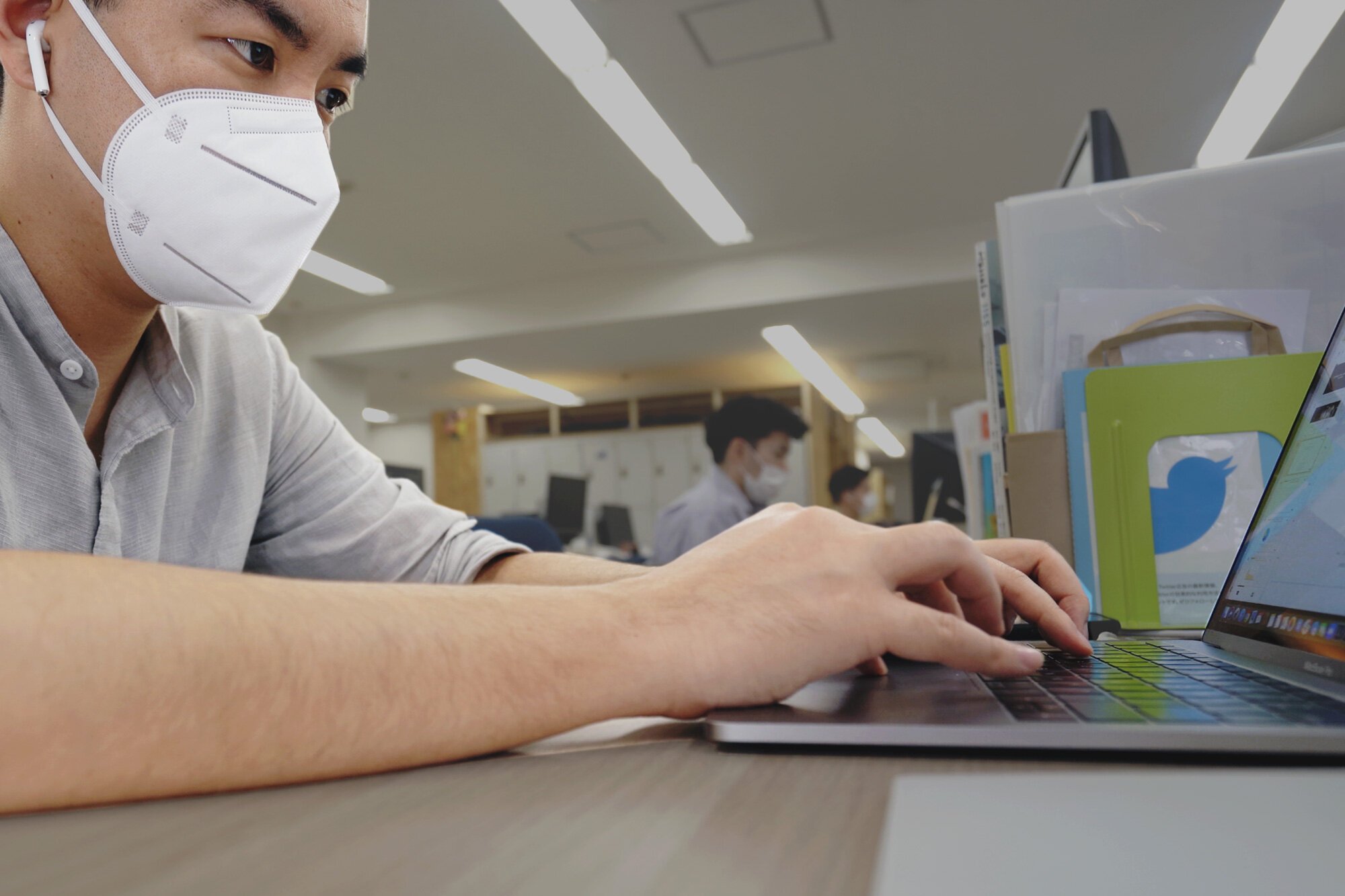

First Day Back in the Tokyo Office After Lockdown

What it’s like to go back to work in Tokyo after the COVID-19 / Coronavirus pseudo-lockdown.

Living in Japan as a Japanese-American

My experience living in Japan as a Japanese-American, both in the countryside and in the city.

Working in Japan Can Be Lonely

Due to language, cultural and mindset barriers, working at a Japanese company as a foreigner can be unintentionally lonely at times.

How Brands in Japan are Responding to COVID-19

What some brands and celebrities in Japan are doing in reaction to COVID-19/Coronavirus.

Working From Home in Tokyo

A look at working from home in Tokyo, as the city is now in a quasi-lockdown and tries to reduce person-to-person contact by 70%.

Japanese Celebrities to YouTube Stars: Haruna Kawaguchi

Haruna Kawaguchi is the latest Japanese celebrity to become a YouTuber.

Life in Tokyo During the Coronavirus Pandemic

How it’s like living and working in Tokyo during the COVID-19 / Coronavirus pandemic.

Typical Workday Lunch Costs in Tokyo

What my typical lunches on Tokyo workdays are like and how much they cost.

Why Japan Has Strange English Ads

Why big companies in Japan use strange English in their ads - My thoughts after working in a Japanese marketing agency

What New Years in Japan is Like

Spending the full New Year’s holiday in Tokyo for an authentic Japanese New Year’s experience.

Instagram in Japan in 2019

All about Instagram use in Japan in 2019. Information from the Instagram Day Tokyo 2019 event.

What You Get in Tokyo for $950/Month

What is a typical studio apartment in central Tokyo actually like? My approx. $950/month apartment in Setagaya, Tokyo.

How I Found My First Apartment in Tokyo

The process I went through to move to Tokyo and find an apartment to live in.

10 Years Living in Japan - A Reflection

This is why I moved to Japan and why I’ve stayed for 10 years. The plan was 2 years.

About Japanese Students Cleaning Their Schools

Japan is praised for having their students clean their schools. Here’s my experience seeing it firsthand.

Valentine's Day Differences in Japan That You Can See

Girls give guys chocolates and a few other easy-to-see differences in Japan on Valentine's Day.

Why Street Photography in Japan Can Be Difficult

A lot of times, photography in public and private spaces aren't so different.

Japanese and Social Media — A Little Different

Japanese have adapted to using international social networks, yet, their preferences and usage differs a little.

Things About to Start Trending Amongst Japanese Teenage Girls in 2017

Apps, people and businesses that may begin trending in Japan in 2017 amongst teenage girls.

Finding a Job in Japan

The way I found a job in Japan is an often unknown and underused tool. I explain it here.