Why Moving Back May Be Hard After Living Abroad

Here are some common challenges American expats may face when moving back to the U.S., based on my personal experience.

New Year’s Differences: Japanese vs Japanese-American

Here’s how Japanese in Japan and Japanese-Americans in Hawaii celebrate Japanese New Year’s differently.

Japanese-Americans: 4th vs. 2nd Generation

A conversation revealing differences between 2nd and 4th generation Japanese-Americans.

The Japanese Versions of Hawaii Snacks

There are many Japanese-influenced snacks in Hawaii. Here are the Japanese versions of them and their histories.

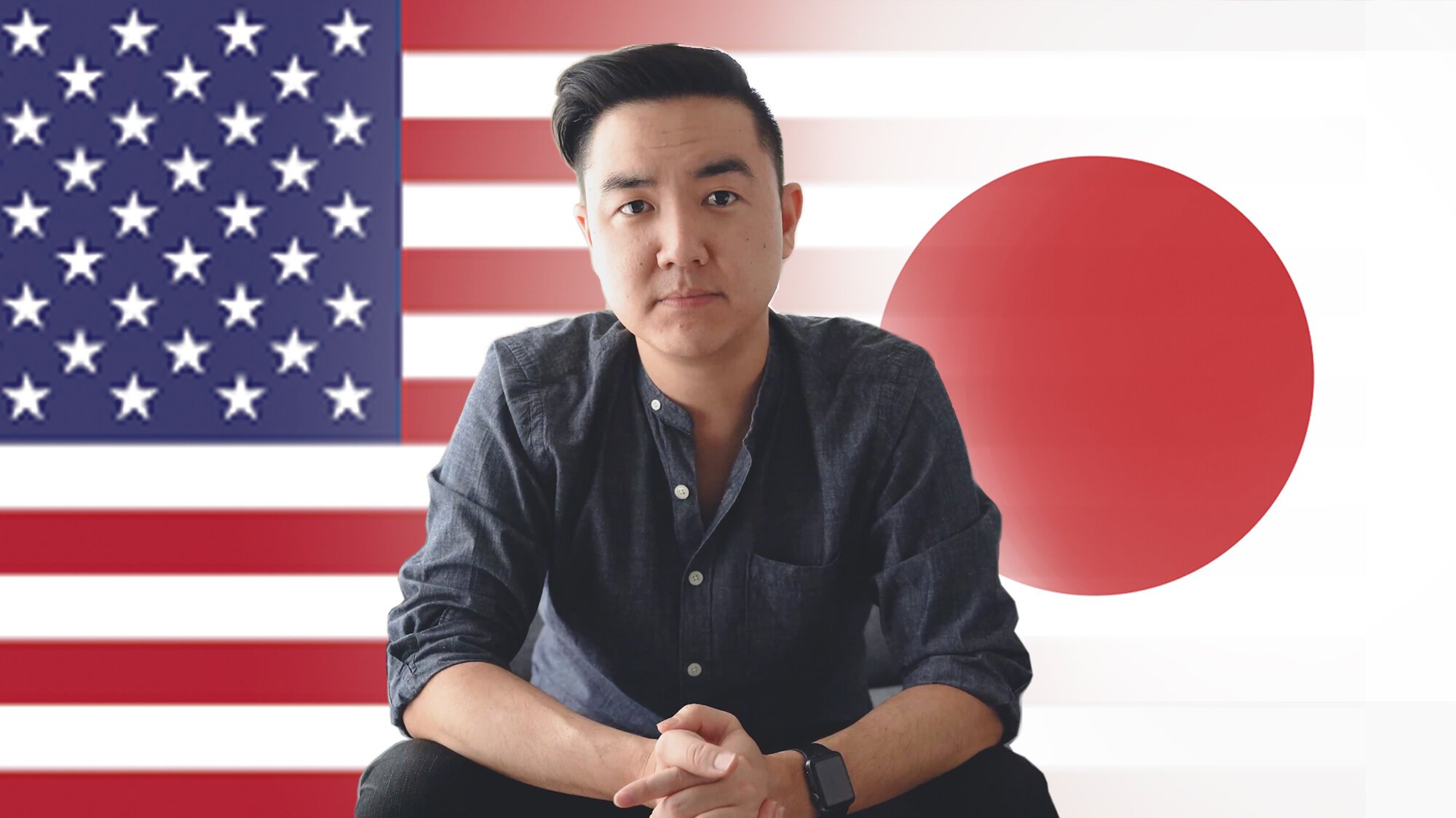

Living in Japan as a Japanese-American

My experience living in Japan as a Japanese-American, both in the countryside and in the city.